The growth of wealth fuels the growth of wealth inequality. And if the “world has never been wealthier,” inequality in housing has become a global issue among those that dominate 21st-century socio-economics.

The twentieth century was a boom time for cities around the world. People, industries and money flooded to economic hubs, fueling expansion faster than urban planners could negotiate it. Land and property prices — particularly in capital cities — were pushed ever higher, forcing poorer residents further afield. Gentrification is an old model that is gaining a new lease of life as urban dynamics shift again in light of post-pandemic economic developments, with low-wage service jobs failing to re-materialize.

On the other hand, those who can , buy — and then they buy again. “Housing isn’t housing,” says Richard Ronald , professor of housing and chair of political and economic geographies at the University of Amsterdam. “Housing is an investment good. It’s a pension.” Unfortunately, this model has boosted luxury home stock while compounding the lack of affordable housing across many global cities.

To paint a clearer picture of how the affordable housing crisis is playing out globally, MoverDB.com analyzed price trends. They found the balance of low-cost and high-cost homes in capital cities around the world.

About This Study

To calculate the percentage around the world, MoverDB.com began by finding popular local real estate websites in each capital city, adjusting the price filter and recording the number of lost-cost and high-cost properties. We defined low-cost housing as that which costs less than half the median home price value in its city and high-cost housing as that which costs more than double the local median price.

Key Findings

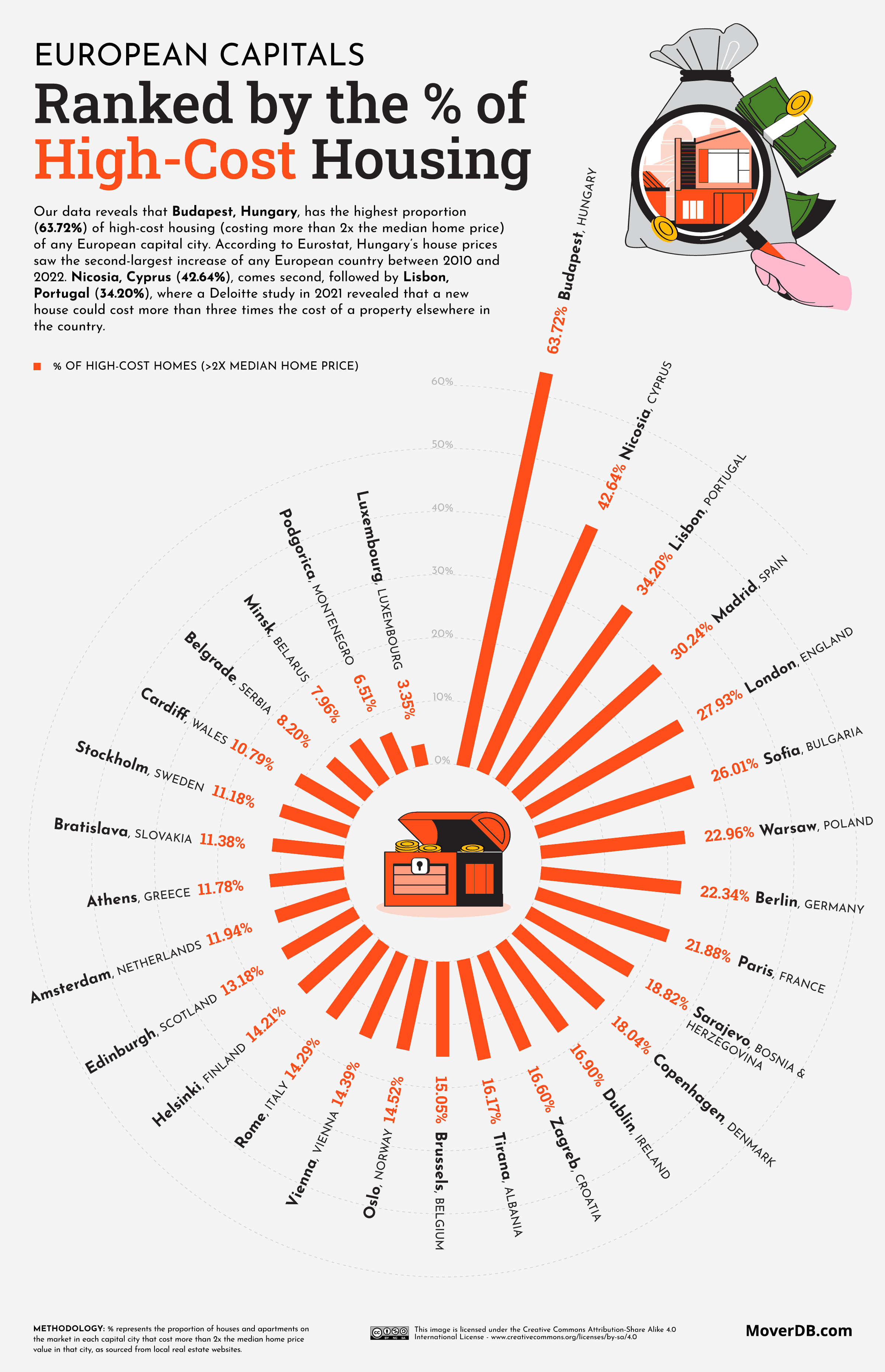

- 63.72% of all housing in Budapest, Hungary’s capital, costs more than twice the median price of homes in the city — the highest split of high-cost housing in any global capital.

- London has the fifth highest concentration of high-cost housing in Europe (27.93%).

- The Brazilian capital of Brasilia has the highest split of housing that costs less than half the local average (50.13%).

- Cyprus’s capital, Nicosia, has the lowest percentage of low-cost housing of any global capital (0.35%).

Half of All Housing in Brazil’s Capital is Low-Cost

Some 75% of the world’s population is forecast to live in urban areas by 2050, with the speed of

Urbanization being the most profound in developing countries. Yet there are already 850 million people living in slums and other “informal urban settlements,” and “in some megacities of low- and middle-income countries, almost 80% of the total population lives in slums,” according to researchers.

Click here to see the image in full size

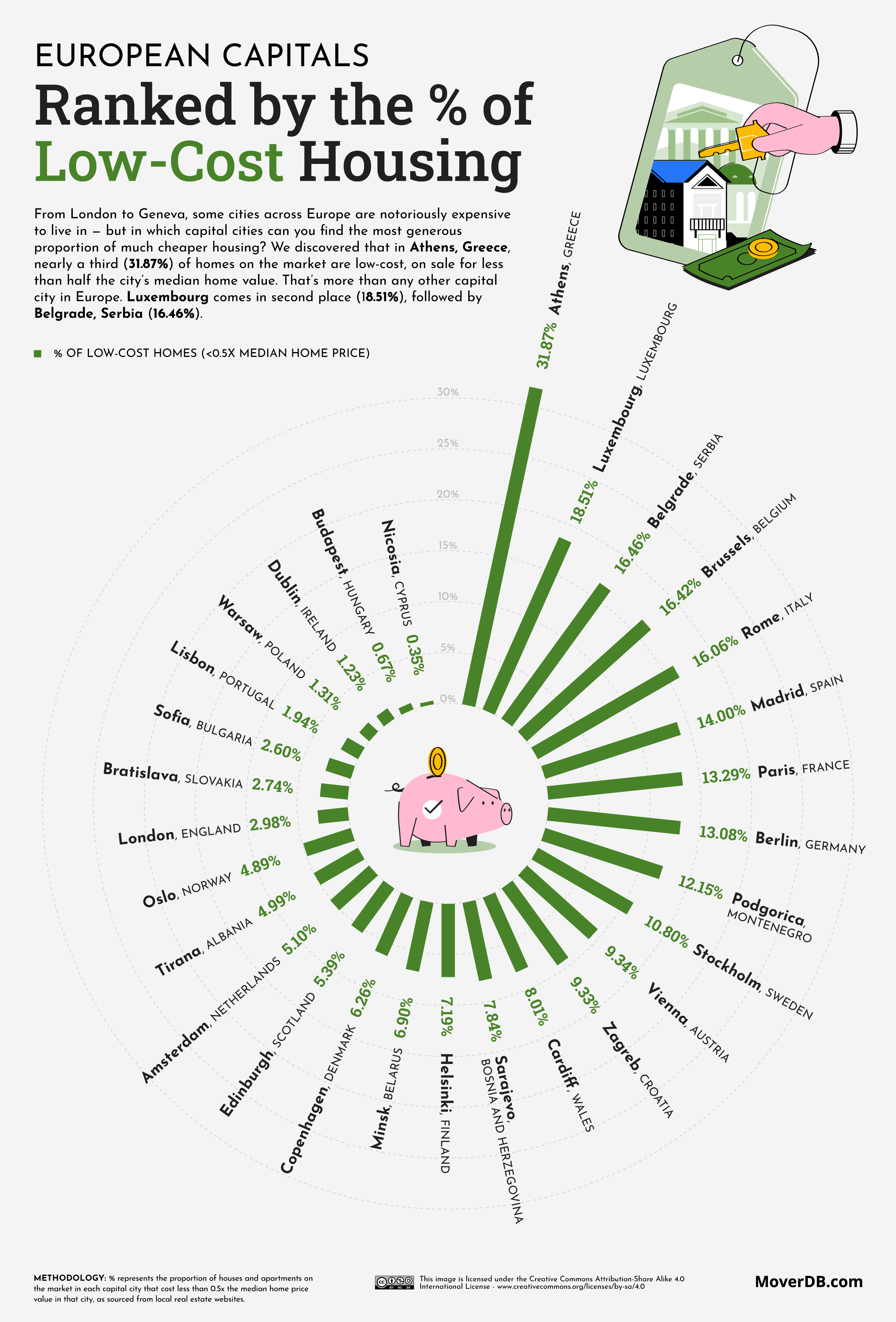

In Brazil, rapid expansion has made the country a major international economy. Still, the housing deficit across the country affects 28.5 million people. However, in the capital of Brasilia, half (50.13%) of the homes for sale are low-cost, i.e., sold at less than 50% of the average local price. Only one European city makes this list, but eight of the ten capitals with the least low-cost housing are in Europe. Worst-served is Nicosia in Cyprus (0.35%).

Click here to see the image in full size

Nicosia also has the world’s fourth highest level of high-cost housing (42.64%). The Cypriot government is presently trying to address some of the worst living conditions in Europe, with the ruling party’s president Averof Neofytou stating that “we have to design our future housing policy with focus on affordable social housing as well as by launching funding programs that will facilitate access to homes, especially for our youth.”

London Has Europe’s Fifth Highest Level of High-cost Housing

London has the fifth highest level of high-cost housing in Europe (27.93%) but the ninth lowest level of low-costing housing in the world (2.98%). The Urban Reform Institute reports that London has the eleventh worst housing affordability levels of any major market in the world. The UK’s stark rich-poor divide is exemplified by contrasting experiences in the borough of Tower Hamlets, where more than 20,000 families families are on the waiting list for social housing. There is a 43% rate of child poverty, despite being home to the major financial district of Canary Wharf — where bankers can pay upwards of £600,000 for a studio flat.

Click here to see the image in full size

“Housing wealth has displaced other forms of capital in a number of developed economies since 1948 and has contributed to growing wealth inequality,” according to a report from Centre For Cities. The effects of this growing divide are often most pronounced in capital cities but also between capitals and regional cities since housing wealth tends to be less mobile than other forms of wealth.

Click here to see the image in full size

There is an ‘odd couple’ with the highest rates of low-cost housing: the capitals of Greece, one of the lowest GDP nations in Europe, and Luxembourg, which has the continent’s highest GDP. However, the Greek capital is ahead by a significant margin despite a decline in social housing over the years. Athens’ iconic polikatoikias were constructed during a “spontaneous, extra-governmental building boom” during the post-war period as a means for pleasant, affordable housing. They have proved a durable solution for low-income citizens. However, socio-economic shifts and the fallout from the credit crisis have warped the market, with locals gradually being priced out by wealthier buy-to-Airbnb investors.

A Global Crisis On the Doorstep

While the housing crisis may have its most profound effects in developing countries, the world’s wealthier capitals are among those presenting unprecedented obstacles in the wake of the pandemic. “Half the middle classes are richer than they ever thought they would be,” as Saskia Sassen — the urbanist who gave us the phrase “global city” — puts it, “and half are poorer.” It’s a problem all over, with 90% of cities sampled for a recent survey considered unaffordable according to common standards.

Land quotas, the repurposing of vacant properties and sustainable low-rent energy solutions, such as green roofs and solar panels in new builds, are among proposed counter-measures for an issue that has no prospects of going away any time soon — as long as the basic right of safe, affordable housing is shackled to the blight of wealth inequality.

METHODOLOGY & SOURCES

We set out to find the % of low-cost and high-cost homes (apartments + houses) in capital cities around the world. We began by finding popular local real estate websites in each capital city (e.g., Zillow for Washington, D.C.), toggling the price filter and recording the number of lost-cost and high-cost properties.

Using the median home price value for each capital city as sourced from a previous project (converted from USD using ExchangeRate.com), we set the following parameters:

• Low-cost housing = housing that costs less than 0.5x the median home price value

• High-cost housing = housing that costs more than 2x the median home price value

From each real estate website for each city, we could then retrieve the following:

• Total number of properties (all houses and flats, but not ‘land’) for sale listed in that capital city

• Number of properties with the ‘low-cost’ filter applied

• Number of properties with the ‘high-cost’ filter applied

This allowed us to calculate the number of low-cost and high-cost properties as a % of all properties within each city.

Dimitry says

> 63.72% of all housing in Budapest, Hungary’s capital, costs more than twice the median price of homes in the city — the highest split of high-cost housing in any global capital.

Sounds strange. By definition, the median is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a data sample. 67% of the values cannot be greater than the median.

If we are talking about the average value, then it also does not converge according to the calculations. The maximum of 50% can be twice the average value, and this is provided that the remaining values are 0.